The cost of predictability in an age of political and technological liminality

“The best way to predict the future is to create it” – This quote, attributed to so many visionaries, might be the most paradoxical business wisdom of our time.

Why? Because there is not such as a future in the singular tense.

The idea of a ‘predictable future’ belongs to scientific positivism of the past. There are multiple futures, as Jennifer M. Gidley explains, “the concept of multiple futures explains…why pluralism is important for the democratisation of the future.”

We’re obsessed with predicting, forecasting, and controlling what comes next, yet we’re increasingly terrible at it. Perhaps because we still bet on one future when anything is possible.

My father is a designer and artist who worked for around 30 years in a company that imported technology from Japan in the early 70s, rebranding it for the European market. I witnessed two pivotal moments when this company had the opportunity to transform from an import-export business into a tech leader.

In 1983, the executives gathered around a table, studying a promising new opportunity, one of the first personal computers available for import to Europe. Someone claims it will “revolutionise everything” but they decide against it.

Their reasoning seemed sound at the time: the market wasn’t ready, the technology was unproven, the risks too high.

A few years later, they face another decision: importing one of the first digital cameras (nobody anticipated that digital photography will reshape a huge industry…ask KODAK). A new camera, resolution: 320×160 pixels. No screen. Clunky as a brick.

They pass again, confident that traditional photography would remain dominant. The future, they believed, was predictable.

Smart decisions? Terrible mistakes? Both? Neither?

The beauty of this isn’t in judging their choices, but in understanding how even well-informed decisions can miss transformative moments. Their experience mirrors what many organisations face today, but with stakes that have grown exponentially higher.

There are moments of higher predictability and others with less. Today, more than ever, we find ourselves in a period of profound uncertainty, one that won’t shift until we address the fundamental challenges facing our planet, environment, and humanity.

Many organisations prefer not to see this reality, choosing instead to maintain the status quo. If we would apply the terminology of trauma psychology, their behaviour follows a familiar pattern: they’re experiencing what specialists would recognise as classic responses to overwhelming change.

Some remain in the “impact” or “shock” stage, where disbelief and dissociation dominate. Others have moved to the “acute” or “rescue” stage, reacting emotionally with fear, anxiety, anger, or helplessness.

Look at how many companies respond to climate change mandates or digital transformation – the parallel to trauma responses is striking.

This raises a crucial question: If we can’t exactly predict the future, how can we make meaningful decisions?

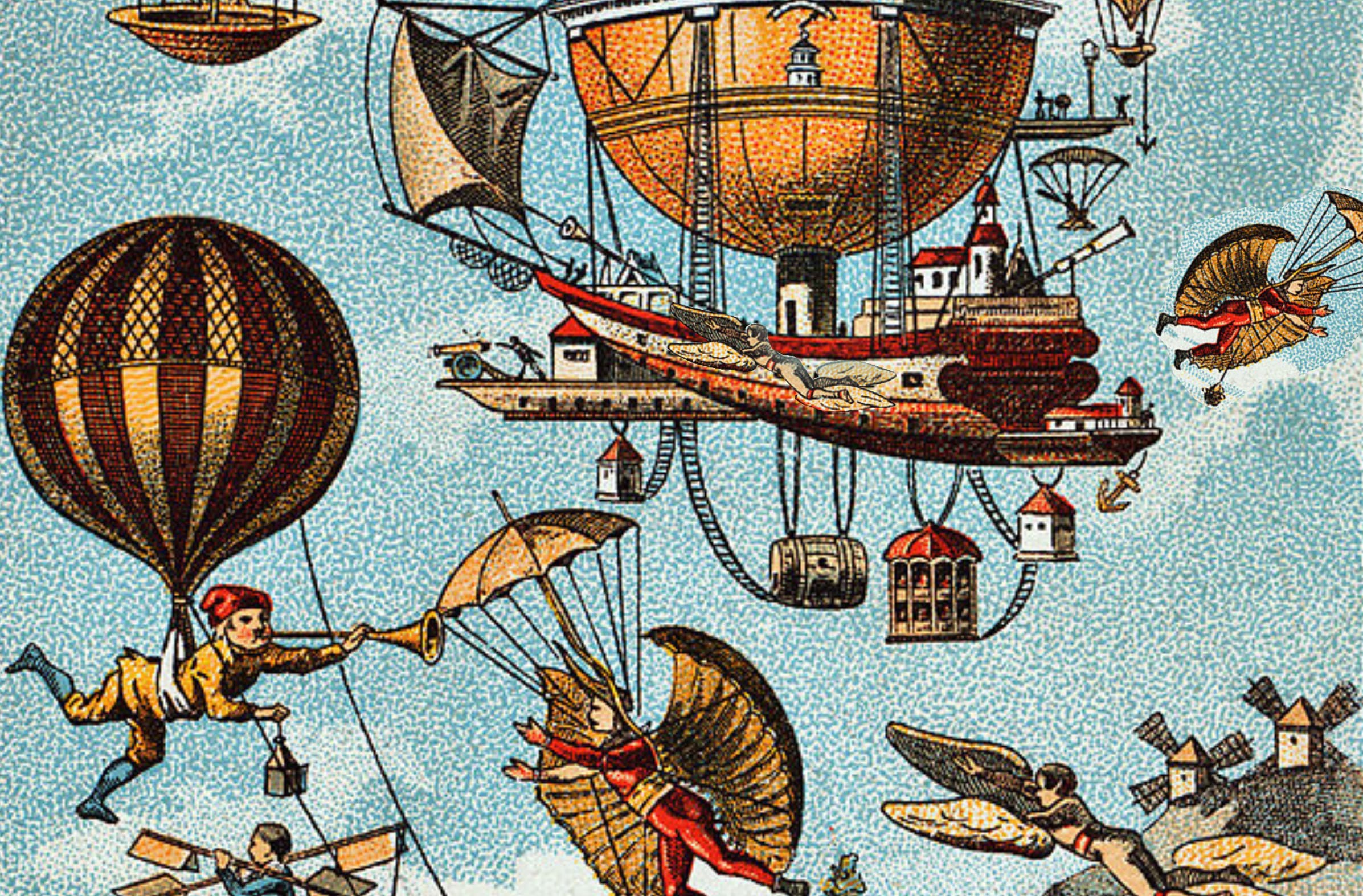

What makes our current moment unique is that we’re not just experiencing change, we’re living in what anthropologists call a liminal space, a threshold between what was and what will be. This isn’t just another period of transition – it’s a fundamental reimagining of how we operate:

- Old systems are failing but new ones haven’t fully formed

- Traditional metrics of success feel increasingly hollow

- The pace of change has overtaken our ability to process it

- Interconnected challenges demand integrated solutions

To navigate this future effectively, we should move beyond traditional forecasting and adopt a futures thinking mindset that works with uncertainty rather than trying to eliminate it.

To navigate complexity effectively, we must rethink traditional approaches to planning and prediction. This means developing frameworks that help us maintain and work with multiple possible futures, adjusting our strategies as new information emerges. Organisations that thrive in uncertainty tend to be those that can balance structured exploration with flexible response.

Futureing itself operates at different levels, depending on our intent:

- Anticipating: Extending what is already known to identify immediate opportunities and risks

- Envisioning: Exploring how current trends and new possibilities might shape what comes next

- Discovering: Finding the new or overlooked by questioning fundamental assumptions

- Shaping: Imagining and influencing what comes next through deliberate action

The key is making futures thinking part of our everyday practice rather than an occasional exercise. This means balancing qualitative and quantitative inputs, as relying purely on numbers and probabilities often limits our perspective and misses the value of structured exploration.

When mapping out possible futures, several elements are essential:

- Sensing and scanning: Spotting what’s emerging, changing, or staying the same

- Sense-making: Finding patterns and insights within what we observe

- Scenarios: Building future models to test different possibilities

- Storytelling: Bringing stakeholders into the conversation

- Assessment: Learning from the process and recalibrating as needed

Beginning doesn’t require a complete organisational overhaul.

Let us start here:

- Creating space for regular horizon scanning in your team meetings

- Developing simple scenarios around key decisions

- Questioning assumptions about what’s “certain” in your industry

- Building a culture that views uncertainty as an opportunity rather than a threat

Remember the company my father worked for? Their story isn’t about failure – they survived and thrived in their way.

But today’s decisions carry greater weight because our challenges are more substantial and imperative. The question isn’t whether we can predict the future perfectly, but how we can build better capabilities for navigating uncertainty.

What if we stopped treating uncertainty as a risk to manage and started seeing it as a material to build with? After all, evolution happens during and after states of liminality. The organisations that thrive won’t be those that predicted the future perfectly, but those that developed the capacity to adapt and evolve alongside it.

Ready to explore how your organisation can navigate uncertainty more effectively?

Talk to us, let’s have a conversation about thriving in liminality.